Patagonia’s 2025 Work in Progress Report opens with a statement from CEO Ryan Gellert: “Patagonia is a paradox. Our charter mandates we follow social and environmentally responsible practices, yet every product we make takes irreplaceable resources from the planet. Our existence seems counter to our purpose. That tension is not lost on us.”

It’s a stark acknowledgement of the contradictory role Patagonia plays in a global system built on extraction. But the report also offers a detailed map of what is working and what is not, even when you are trying harder than almost anyone else in the industry.

You could read this report in a number of ways, and given the amount of press Patagonia generates, you’ll probably see a variety of takes. Some as a celebration of progress, others a critique of ambitions that are currently falling short. Both readings would be accurate. Both would be incomplete.

The outdoor industry has spent years putting Patagonia on a pedestal as proof that a different kind of capitalism is possible. But I think this feels like the first time they’ve more directly acknowledged the true scale of the walls standing in the way of success.

The 6% Problem

In 2018, Patagonia set a goal to source 50% of its synthetic materials from “secondary waste” such as fishing nets, textile scraps, and agricultural waste by 2025. They reached 6%.

That is not a typo. Six percent.

The report maintains that setting such an ambitious goal was intentional. “We wanted to move past single-use plastic bottles as our main recycled synthetic waste stream.” But it’s genuinely hard to take mixed, contaminated waste and transform it into high-quality technical fabric. Roughly 80 percent of Patagonia’s recycled synthetics still come from plastic bottles, because bottles are the only waste stream with infrastructure that actually works (currently). This means Patagonia remains deeply tied to the virgin plastics economy even as they try to build alternatives.

And when it comes to closing the loop on the clothing that they sell, they get back less than 1% of what they make. Of what does return, only about 20% can be recycled again. The rest is sitting in warehouses in Reno, Europe, and Japan, waiting for systems that do not exist yet.

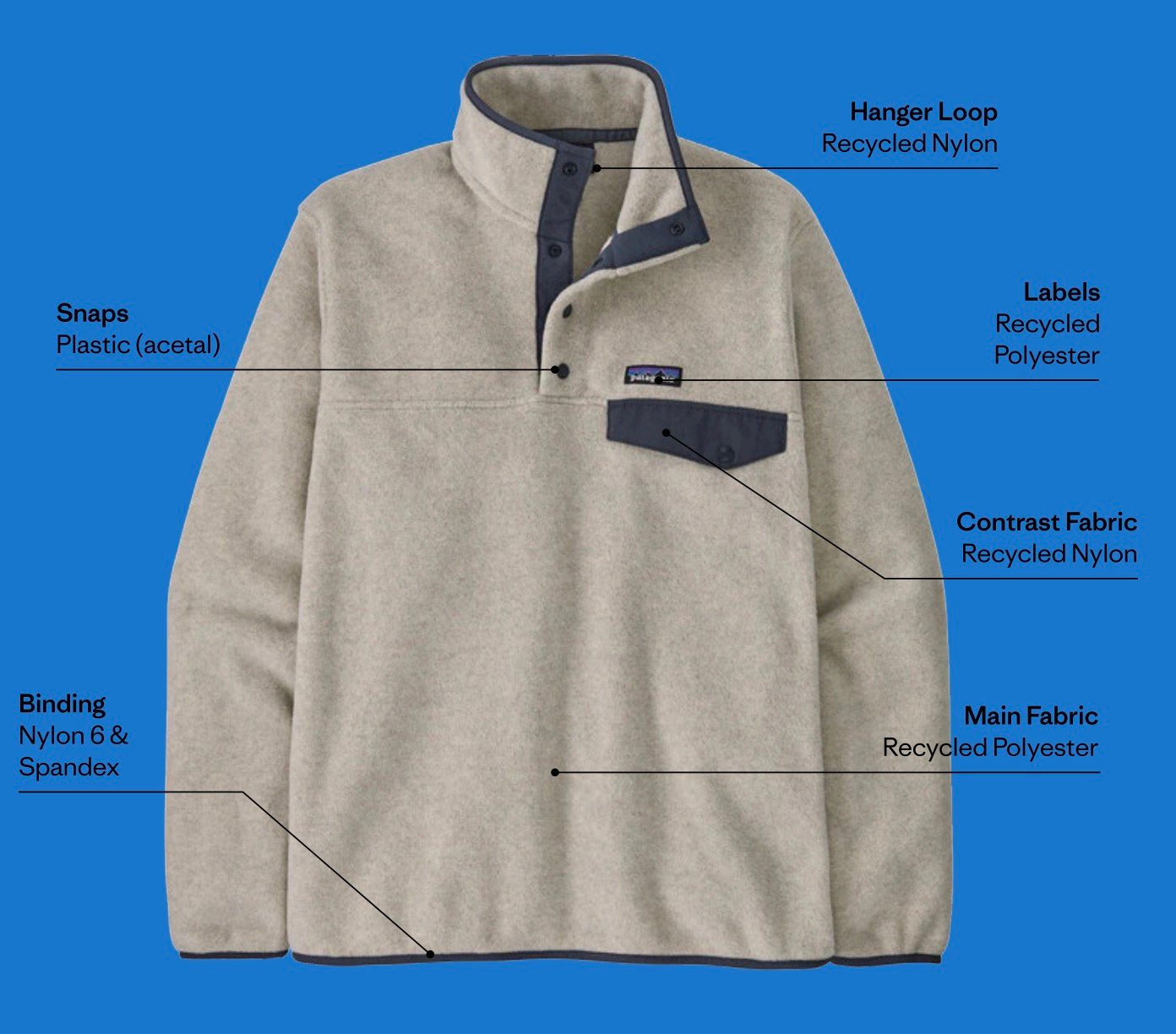

Patagonia’s Synchilla Snap T fleece, made from 95-100% recycled polyester, produced 209,000 pounds of scrap material for 395,000 pullovers in FY2025. And once that pullover is bought, worn, and hopefully returned for recycling, there are a few key issues that challenge its suitability for recycling. The pullover has five different trim materials, all of which need removing before recycling; none of those currently have end-of-life solutions. They go into storage.

This is Patagonia, the company that’s been thinking about product recycling for about as long as anyone, and they still can’t close the loop on a “simple” fleece.

That doesn’t mean it’s impossible. Salomon’s Brigade INDEX helmet achieved full recyclability by designing around a single material family from the start. When customers return the helmet, it can be ground down and recycled without disassembly. But, that’s just one case, albeit a good one. Some product categories might allow for the material simplification that makes recycling actually work better than others.

Why Scope 3 Emissions Matter

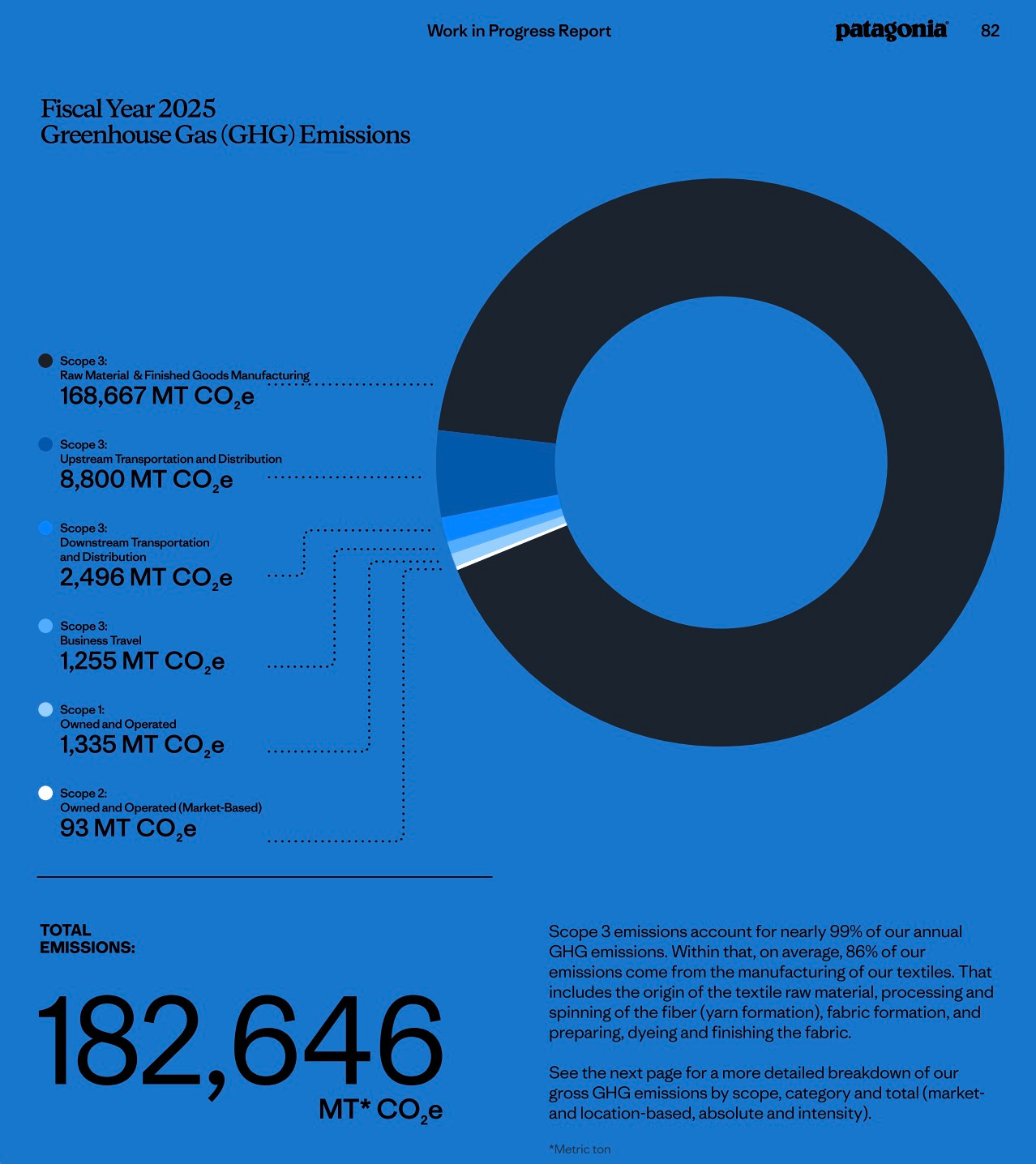

The recycling challenge is primarily technical: a confluence of current materials science and recycling abilities/economics. But Scope 3 emissions reveal something fundamentally harder. They reflect the limits of what any one company can control in a globalized supply chain. The vast majority of environmental impacts are happening in parts of the supply chain no single brand can fully see, let alone control.

Scopes 1 and 2 cover emissions from owned facilities and purchased electricity. For Patagonia, those are tiny. Scope 3 includes everything else in the product lifecycle: fiber production, material processing, dyeing, shipping/transportation, product use, end of life disposal. It represents 99% of Patagonia’s total emissions. So, while it’s laudable that “98% of [Patagonia’s] owned and/or operated electricity comes from renewable sources”, it’s not much of a dent in their overall emissions.

The Supply Chain We Can’t See

Scope 3 emissions are often things that individual corporations don’t have very much control over. Energy choices at production facilities. Global shipping logistics. The apparel supply chain is not built for traceability.

A single jacket might include cotton from India, recycled polyester from Taiwan, nylon from Japan, and zippers from China, all assembled in Vietnam. Energy grids differ from region to region. Regulations change across borders. Tracking is a muddy patchwork of educated guesswork, trust, and incomplete data stitched together into something that is often presented like certainty.

But that doesn’t mean Patagonia isn’t trying to move the needle.

One example from the report: they are running a pilot program with a supplier in Taiwan to replace a coal boiler with a steam boiler. Patagonia helped fund the equipment, which is projected to reduce that facility’s emissions by about 27,500 tons a year, roughly a 30 percent reduction. This approach has the potential to lower emissions for every brand that uses that factory, not just Patagonia. They’ve has been working in concert with other brands like Burton, New Balance, REI, Gore and the Outdoor Industry Alliance (OIA) to fund studies into textile mill electrification, but it is still a small effort in the context of a massive industry.

Even that approach reveals the limits. Why would a supplier overhaul its energy infrastructure if Patagonia is only a small part of its overall capacity?

The brands with the most purchasing power to drive supply chain change are often the ones least committed to sustainability, while the committed brands lack the scale to force systemic transformation. Patagonia can work with individual facilities, demonstrate proof-of-concept, and hope these practices spread. But they can’t reshape the energy infrastructure of entire textile manufacturing regions in Asia.

The report makes it clear that Scope 3 is not just a sourcing problem. It is an infrastructure problem that demands investment across entire regions and countries. It is a data problem where reliable emissions measurement often does not exist. It is a relationship problem that requires years of collaboration and trust.

Patagonia’s efforts are not enough to deliver the speed and scale of decarbonization the climate demands. That will require public investment, policy pressure, shared standards, and infrastructure that no individual company, even one as committed as Patagonia, can build alone.

What’s working

While Patagonia struggles with recycling infrastructure that doesn’t exist and supply chain emissions they can only partially influence, all is not lost. Despite failures and challenges, Patagonia has built working models for the circular economy, material investments and more.

Their Reno repair facility fixed nearly 175,000 items in FY2025. In Europe, they helped found the United Repair Centre, which employs resettled tailors and repaired 14 thousand Patagonia items in FY25. Their Worn Wear program generated $13 million in revenue and kept more than 212,000 products in circulation instead of requiring new production. Honestly, those numbers are significantly larger than I would have expected, and a testament to how programs like this can work.

This is circularity that scales because the systems already exist and resale has built in incentives. Customers trade in gear and receive credit or repaired gear. Patagonia retains customer relationships and avoids manufacturing new products. Yes, there are challenges with reverse logistics (most companies aren’t set up to process products flowing backward through their supply chain instead of forward), but these are surmountable. And companies like Archive and Tersus have popped up to service the space. The economics align in a way recycling still does not.

Over 93% of Patagonia’s polyester and 89% of nylon are now recycled. They provided seed funding to in 2014 that helped develop the NetPlus, “a 100% recycled material that reduces the need for virgin plastic and helps prevent used, discarded fishing nets from polluting our oceans.” More than 150 styles now use NetPlus recycled fishing nets, which has since expanded to partners like Nike, Yeti, and Costa. 29 more use ECONYL® 100% recycled nylon, an alternative sourced from industrial and post consumer waste.

And, after almost two decades of R&D, Patagonia has eliminated PFAS (polyfluoroalkyl substances, aka “forever chemicals) across all new products. Given how widely these chemicals are now understood as a health risk, that milestone matters. It’s a push that has had wide-ranging effects on the regulatory and manufacturing of the entire outdoor industry.

I’m not even touching on their work around corporate responsibility, advocacy, trade practices, and conservation, which could fill another newsletter.

These aren’t just small wins. They’re the kind of operational changes that require years of relationship-building, technical expertise, and financial commitment that many brands can’t (or won’t) make.

Recalibrating Expectations

Patagonia is still selling jackets, and more of them than ever. Critics are not wrong to point that out. But they are also repairing 175,000 items a year, keeping hundreds of thousands of products in circulation, eliminating PFAS, investing in decarbonization and conservation, and openly documenting where they are falling short.

The pedestal we have put Patagonia on has attracted both adoration and backlash. But there’s a simple truth here. Patagonia is a company trying to do better inside a system that makes doing better extraordinarily difficult. They have succeeded in ways that matter, and they have run into ceilings that will not move without structural change.

Patagonia is a company trying to do better inside a system that makes doing better extraordinarily difficult.

The industry needs Patagonia to keep pushing, experimenting, and showing what is possible. But even Patagonia cannot build the future alone. Circularity and decarbonization require regulation, shared infrastructure, and coordinated investment.

Patagonia knows this. They’ve been transparent about it. The real question is whether the rest of the industry (both outdoor and wider textile/fashion), and the policymakers who shape it, are willing to help build what even the most committed companies cannot build on their own.