On September 2, 2024, Michelino Sunseri ran up and down Grand Teton in 2 hours, 50 minutes, and 50 seconds, breaking the existing Fastest Known Time (FKT) by over two minutes. Within weeks, he had been charged with a federal misdemeanor. In May 2025, he went to trial. In September 2025, he was convicted. And last week, he received a presidential pardon. No, really. A PRESIDENTIAL PARDON.

All because he cut a switchback.

This wasn’t just about trail ethics. It was about what happens when outdoor performances become spectacle and when Strava posts and record-seecking clashes with the rules that keep public lands intact. The incident became a story not because of the severity of what happened, but because of how it was framed and how the government responded.

The whole thing is bananas, but somehow entirely fitting in 2025.

What Actually Happened

The facts are straightforward. Sunseri, a North Face-sponsored trail runner from Idaho, went for the FKT on the Grand Teton. On his descent, he used a shortcut down an old climbers’ trail that bypasses a series of switchbacks.

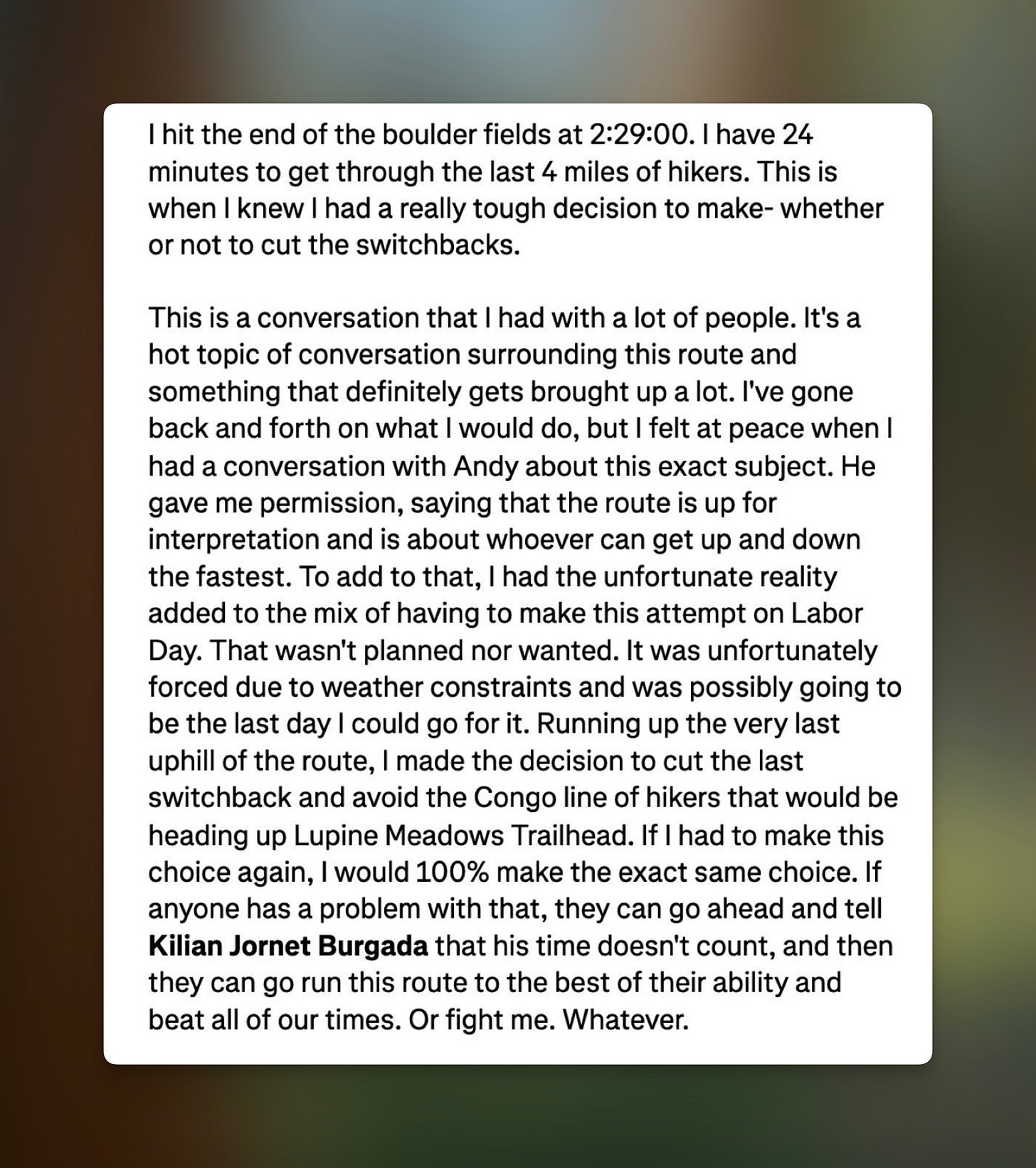

His GPS track showed it clearly. On Strava, he acknowledged it openly: “I made the decision to cut the last switchback and avoid the Congo line of hikers that would be heading up Lupine Meadows Trailhead. If I had to make this choice again, I would 100% make the exact same choice.”

He added that anyone who disagreed was welcome to attempt the speed record themselves, talk to former record holders, “Or fight me. Whatever.”

Unfortunately for him, the trail was closed and marked as such on both ends. The National Park Service was not amused, nor was much of the outdoor community. Though Sunseri offered to help with trail maintenance or improve signage, the Park Service pursued a formal citation.

Grand Teton officials charged Sunseri with violating federal regulations (36 CFR 2.1(b)) prohibiting off-trail travel to cut switchbacks. This is a misdemeanor carrying up to six months in jail and a $5,000 fine. FastestKnownTime.com, the unofficial arbiter of speed records, rejected his time. The North Face scrubbed their Instagram posts about him. Sunseri went from celebrating a record to facing prosecution.

It is worth noting that his defiant Strava post, combative tone, and refusal to acknowledge any wrongdoing likely played a major role in the Park Service’s decision to pursue charges. When you publicly mock regulations while your sponsor promotes your achievement to millions, you are effectively daring authorities to make an example of you.

A Park Service public affairs officer said the case was being taken seriously because of its public nature: a sponsored athlete posting to social media and a brand promoting the content widely. But many felt the federal misdemeanor charge, a proposed five-year park ban, and 1,000 hours of community service were wildly disproportionate to one closed shortcut. In May 2025, on the eve of trial, the NPS operations deputy director sent an email withdrawing support for the prosecution, calling it over-criminalization. The U.S. Attorney’s Office pushed forward anyway.

The case began attracting political attention. The Pacific Legal Foundation represented Sunseri pro bono, and U.S. Representatives Harriet Hageman of Wyoming and Andy Biggs of Arizona, both House Judiciary Committee members, criticized the prosecution as government overreach. Despite this, in September, federal judge Stephanie Hambrick found Sunseri guilty, and sentencing was planned for late October.

Instead, on the day of sentencing, surprise plea deal was proposed: 60 hours of community service, a wilderness course, and a year of probation, with the conviction eventually cleared. But Hambrick questioned whether political pressure influenced the offer from the new, Trump-appointed, U.S. attorney for Wyoming. “It’s an interesting message you send to the public,” she said. “If you whine and cry hard enough, you get your way.” She declined to accept the deal and requested 30 days to review.

But before that hearing could occur, President Trump issued a full pardon in the same week he pardoned individuals convicted of attempting to overturn the 2020 election, cryptocurrency entrepreneurs, and former members of Congress. The judge’s skepticism proved prescient.

A double standard?

While Sunseri clearly broke the letter of the law, how it was handled is up for debate. He was not the first person to cut that switchback during an FKT attempt. Multiple prior record attempts used the same shortcut. Iconic ultrarunner Kilian Jornet cut the switchback on his attempt. None faced charges.

Sunseri’s legal team argued the closure was not adequately marked. Park officials countered that both he and local athletes knew it was closed. Local Jackson Hole athlete Kelly Halpin, who was subpoenaed to testify, said she specifically advised Sunseri not to use the shortcut.

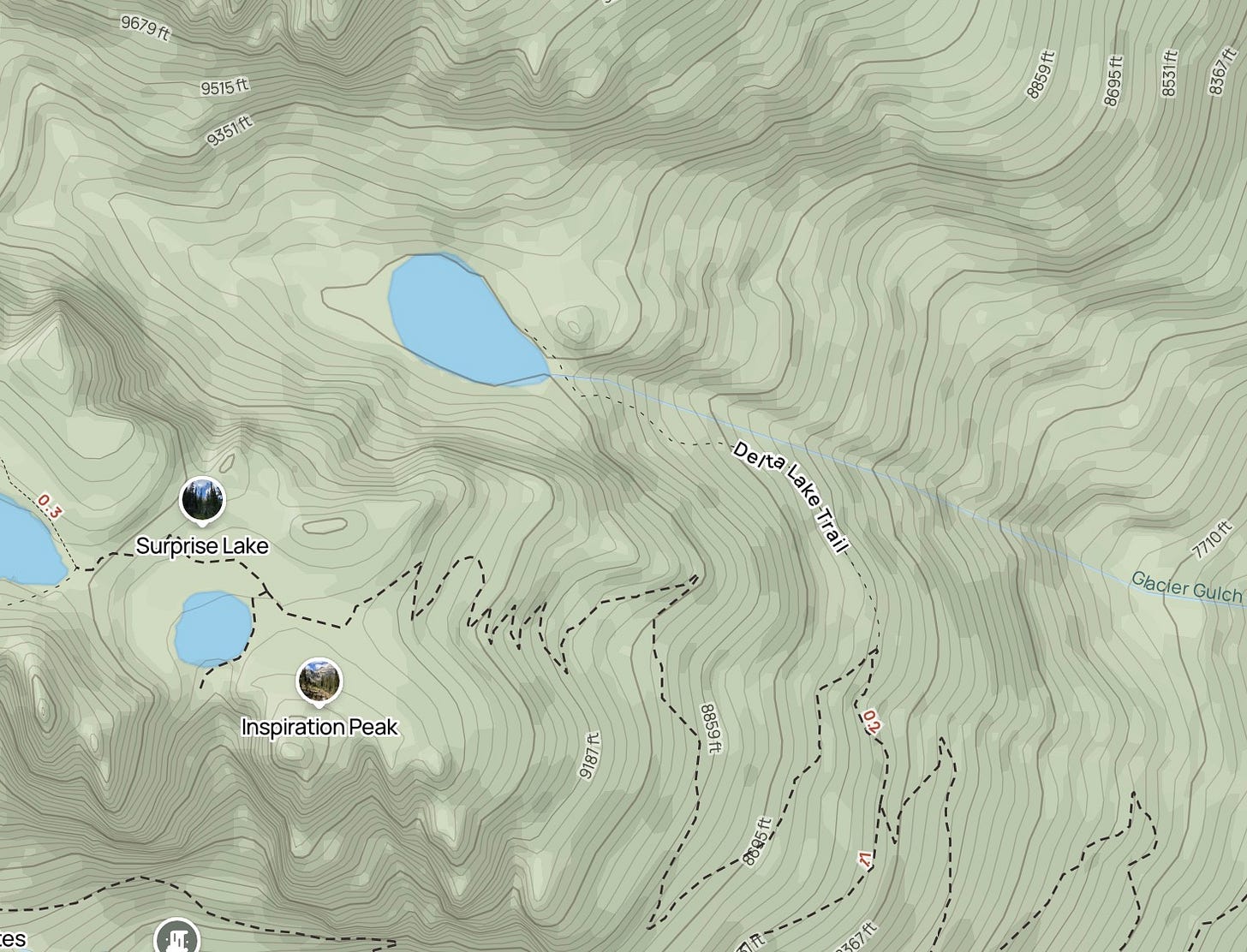

Meanwhile, nearby Delta Lake is technically off-trail, yet hundreds of visitors hike there daily in summer, trampling fragile alpine terrain. The Park Service does not station rangers there writing tickets. Platforms like AllTrails and dozens of blogs promote Delta Lake despite it not appearing on any official NPS maps.

And it is not just Grand Teton. The current “car to car any route” FKT on Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park cuts the official trail significantly, including in lower, clearly marked sections.

But Sunseri did more than cut a switchback. He was part of a production in which crew reportedly blocked parking lots, including handicapped spots, and filmed without permits. Then he publicly bragged that he would do it again. That is not an honest mistake. That is someone acting as though rules do not apply. Casual entitlement from sponsored athletes is a high-profile way to erode shared norms. If a North Face athlete can take over a trailhead and document illegal activity for promotional content, what message does that send?

Still, pushing for the most severe punishments? Continuing prosecution after the National Park Service withdrew support? That’s where things get murky. Most people would agree Sunseri was in the wrong (and acted like a jerk about it), but there’s a valid argument to be made that the prosecution became grandstanding, and eventually backfired.

Switchback culture

If you explained this story to a European runner, they might be confused. In much of Europe, particular in many races in the Alps, cutting switchbacks is normalized. Athletes are expected to choose the most direct line. Here in the UK, fell running has no set course at all. You get up and down however you choose.

But in the United States, our outdoor norms are more conservative. We’ve cultivated a kind of wilderness puritanism, particularly as it applies to National Parks, one born out of necessity. These are some of the most visited natural places on Earth, and they’re managed by agencies with finite staff, shrinking budgets, and an impossible mandate: protect delicate ecosystems while accommodating millions of visitors a year. Strict trail etiquette is one way we try to limit impact. Seemingly small actions, like cutting a switchback (especially if widely shared or normalized), can scale into real damage. Between overcrowding, poor wilderness ethics, and social media, rules are there for a reason.

And yet, the reality is messy. Who among us hasn’t accidentally or intentionally cut a switchback at some point? I’ve spent plenty of time off trail to reach certain peaks or ridge lines. Some things are “clearly” bad, like going off boardwalk in Yellowstone. Others are more vague–a “you know it if you see it” scenario. Things can be messier than guidelines (or Instagram commenters) suggest.

That said, I think what’s unfolded here is not an exploration of the nuance present in backcountry travel, but instead a reframing of the incident as a symbol of government overreach. While many of the loudest critics came from conservative voices wary of federal authority and regulation, frustration with public land management isn’t confined to one side of the aisle. Athletes, wilderness advocates, and access-focused organizations from various political backgrounds have long debated the role of enforcement, trail access, and land-use policy. This case tapped into broader tension over who sets the rules, how consistently they’re enforced, and who gets held accountable.

The end of the story

A sponsored runner pushed boundaries and acted like the rules did not apply. The Park Service responded with prosecution. The legal system continued long after practical value disappeared. Political actors turned it into a symbol. And eventually, presidential power erased any consequence.

What should have happened? Probably a citation, a fine, maybe a short-term park ban. Instead, it became a proxy culture-war flashpoint, one that let Sunseri’s advocates reframe it as a debate over federal overreach, regulation, and personal freedom. That framing likely influenced the administration’s decision to even consider a pardon.

Meanwhile, the Grand Teton remains the same. The switchback is still closed. Delta Lake still draws crowds. The Longs Peak FKT? Still up on the platform that rejected Sunseri’s time.

There’s room for debate over how this should have been handled. But what’s undeniable is that an instance of particularly poor judgment spiraled into one of the most unlikely outdoor stories in recent memory…one that somehow reached the highest levels of American government.