A few weeks ago, I had the good fortune to spend a few days skiing in Chamonix. We got days in at Brévent, Flégère, and Grands Montets, but the standout, by far, was skiing the iconic Vallée Blanche—a roughly 11-mile backcountry route that starts at the top of the Aiguille du Midi and weaves down through the Glacier de Géant and the Mer de Glace. It’s one of those rare experiences that sits at the intersection of wildness and accessibility, one that I’m sure many Mountain Gazette readers have either enjoyed or heard of. A full-on glacial traverse, complete with crevasses and ice walls, yet somehow still doable for strong intermediate skiers with a guide. It’s a wild, and remote experience, even if it’s accessible via a gondola ride from town. It’s spectacular and, increasingly, a snapshot of a changing world.

Our day started at the base of the Aiguille du Midi cable car, where we met our guide, ran through a gear check, and joined a line of similarly kitted folks funneling toward the waiting area (as well as more casually dressed visitors just headed to the top for a photo and an aperol). The cable car itself is an incredible feat of engineering, sending hundreds of skiers, climbers, and tourists over 9,000 feet in elevation every day and ending at a needle-like structure perched on the edge of the void. Even if you’re not skiing or climbing, just stepping out onto the catwalks for a sweeping vista of Mont Blanc and the surrounding mountains is a must-do for any visitor to Chamonix. It’s truly a wild spot.

From the Midi station, a short but exposed ridge walk took us to a small plateau where we put on skis and began our descent. There are multiple variations of the Vallée Blanche, some more technical than others. We opted to extend our day with a detour toward Italy, gaining a bit of extra vert by skinning up one of the lower sections of glacier before dropping back into the main route. There’s a kind of quiet grandeur out there; you’re on a massive glacier plain, surrounded by huge vertical relief, ice, crevassed slopes, and serac walls towering in all directions.

After a stop for a snack, we ripped skins and began the long journey down, starting on open slopes that turned into a bit of route finding and picking the best route through the glacier.

The lower portion of the route flattens and begins to wind through icy luge tracks and braided melt channels. Eventually, we reached the final transition: a set of stairs to a short tram that bumps skiers up to the Montenvers train station, the last leg back into Chamonix proper. This tram is new, opened in 2024 after the old one outlived its purpose. The glacier had simply receded too far to support the old tram.

And that’s kind of the quiet undercurrent of the whole experience; there’s a sense that some things are slowly slipping away.

On our ski, our guide pointed out sections of exposed rock he’d never seen before on the glacier. Yes, it’s been a low snow year, but the broader pattern is unmistakable. You can literally see the changes in the landscape—the older, weathered rock on the cliff sides stands in stark contrast to the fresher, gray stone more recently uncovered by melting ice and rockfall. It’s like watching geology unfold in real time.

According to the Observatoire des Glaciers, the Mer de Glace, France’s largest glacier, has retreated more than 2 kilometers since 1850. Today, it loses 30 to 40 meters per year. The Montenvers train station, where we ended our ski, once sat almost level with the ice. It now requires visitors to descend a series of staircases and a cable car to reach the glacier’s surface.

The Aiguille du Midi isn’t immune. As the permafrost that stabilizes its foundations thaws, the structure (which already seems like insanely precarious engineering) faces increasing maintenance challenges. In some cases, engineers are preemptively melting permafrost to replace it with concrete, hoping to get ahead of the instability. It’s a strange circumstance; the infrastructure that gives us access to these places is being steadily dismantled by the forces we set in motion, and we’re accelerating that shift in order to stabilize it. Seasonal shifts are also shrinking both ski and mountaineering seasons, and some classic routes accessed from here are simply no longer safe to climb.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to Chamonix. Across the globe, iconic destinations are becoming case studies in “last chance tourism.” The Great Barrier Reef has experienced back-to-back bleaching events that have devastated large portions of the ecosystem. In the U.S., Glacier National Park is rapidly losing the glaciers it was named for, with projections suggesting they could disappear entirely within the next few decades. Here in the UK, the skiing in Scotland (yes, there is skiing in Scotland) has become more and more inconsistent, with some resorts struggling to survive.

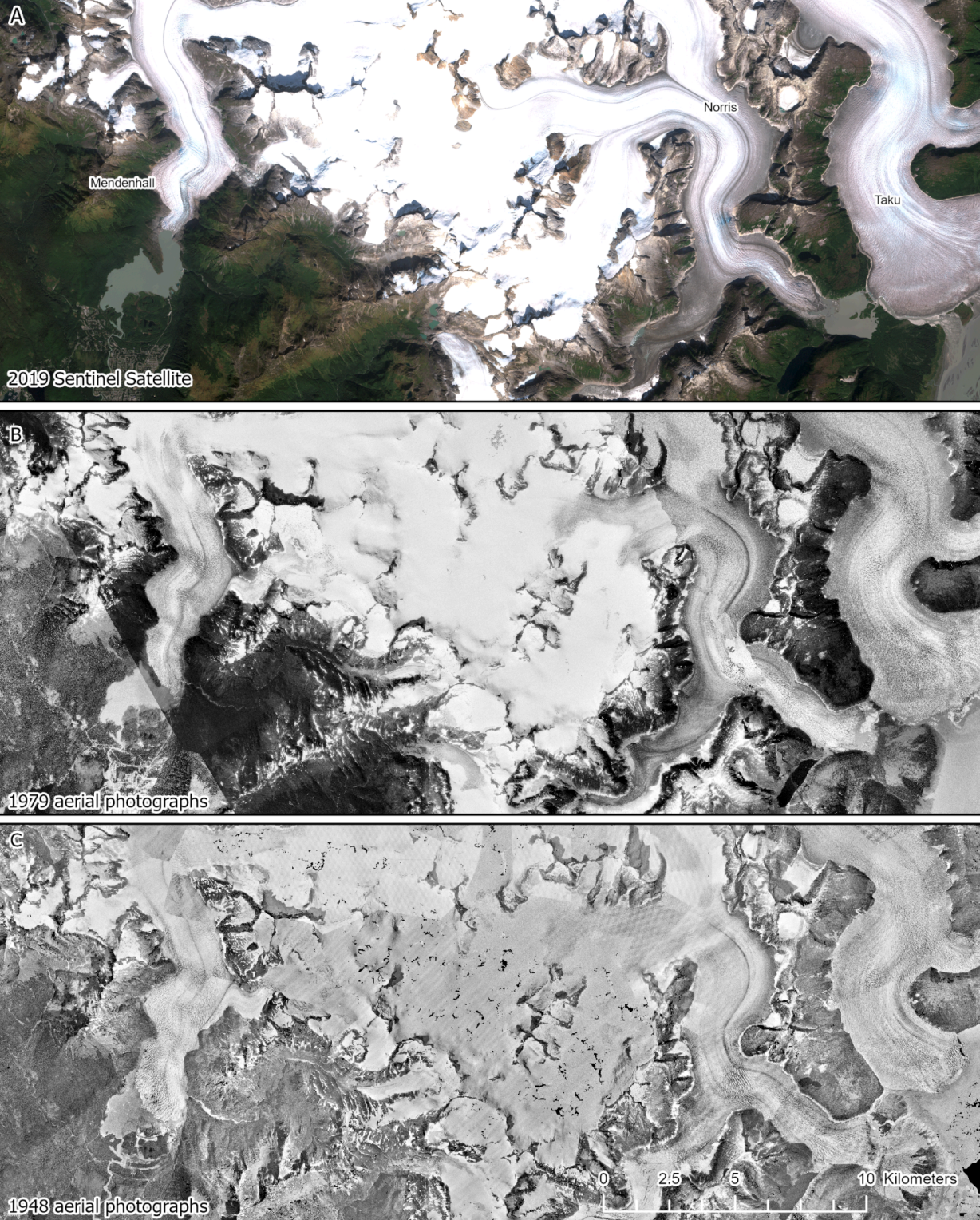

Alaska’s Mendenhall Glacier has lost 1.75 miles in length since 1929. The retreat is accelerating, driven by rising global temperatures, shifting snowlines, and decreasing surface reflectivity, or albedo, which causes the glacier to absorb more heat (Davies et al., 2024). According to glaciologists, this trend signals a threshold response to climate warming, where changes become more rapid and less predictable over time.

The U.S. Forest Service projects that the Mendenhall Glacier could retreat out of view from its visitor center within the next 25 years. To prepare, they’re adopting a long-term plan, including expanding trails, designing new viewing platforms, and weaving climate education into visitor experiences. These shifts reflect a broader challenge across many places and agencies: How do you help people continue to connect with these places, even while they’re changing at such a rapid pace?

Even cultural landmarks like Venice face existential threats, as rising sea levels increasingly flood its historic streets. Mount Kilimanjaro’s once-famous glaciers could vanish within the next few decades. This could change not only the iconic image of the peak, but also has potential ramifications to its trekking ecosystem. The same holds true in places like Ecuador. I climbed several volcanoes there about ten years ago and, even then, there was discussion about how melting ice was affecting the safety and viability of common routes. These places, like the Vallée Blanche, are shifting from bucket list staples to fragile, fleeting experiences, becoming destinations we may have limited chances to see in their current form.

“Current form” might be a key phrase here. Some of these changes won’t be immediately obvious to many travelers. The glaciers around Chamonix will still be spectacular; their retreat is less noticeable at a glance. But what is changing, and often more subtly, is how we experience these places. Ski resorts that once revolved entirely around snow are now extending seasons and investing heavily in summer activities like mountain biking, trail running, and via ferratas. Last year, a historic Swiss ski resort closed for good because decreasing and inconsistent snowfall made operations too difficult. Landscapes once defined by winter may increasingly be explored in running shoes instead of skis. So while the mountains themselves aren’t going anywhere, the way we move through and interact with them is shifting, sometimes dramatically. It’s only a matter of time before the Montveners staircase gets longer and longer and even the most recent tram becomes defunct.

There’s a strange melancholy to it all. I’ve been lucky to travel a fair amount, more than most people, and I’ve tried to let go of the desire to “see everything.” I won’t. I can’t. Chasing everything is more likely to lead to burnout and meaningless checked boxes than any sense of fulfillment or satisfaction. But something about the vanishing nature of these landscapes, or at least the types of activities that they can support, injects in me a sense of panic. Not just the FOMO, but recognizing that these places might become places that live mostly in stories, not lived experiences.